The CEMS community explores the impact of the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) on business leadership and the creation of radical new business models.

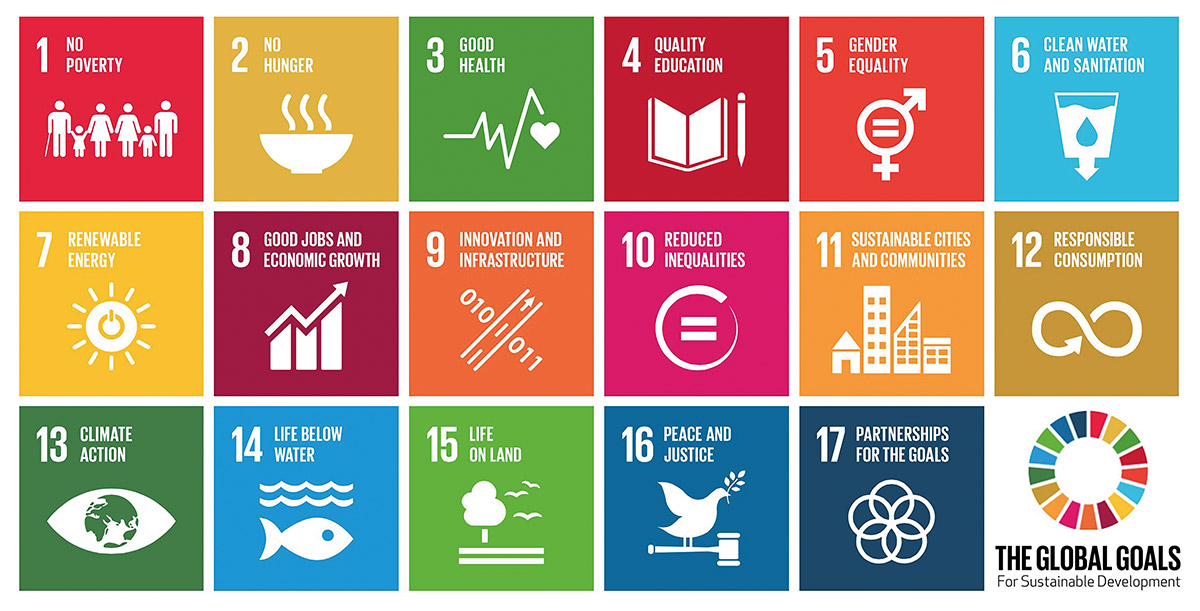

In 2015 a UN global summit launched “Agenda 2030”, with a key element being its seventeen sustainable development goals which, in the words of the UN Charter, “promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom”. The SDGs are essentially an agenda for governments, society and business to create a fairer and more sustainable future for all world citizens. They range from the idealistic goals of “no poverty” and “zero hunger” to calls for “climate action” and “clean water and sanitation” as well as “decent work and economic growth” and “responsible consumption and production”. It is not always clear how companies should respond, but solutions can be found that are relevant for many different industry sectors and markets: there is clearly no one size fits all.

For CEMS Academic Member Schools and for CEMS Corporate and Social Partners, SDGs are starting to inform research and shape the business agenda of the future. The influence of the development goals can be seen in areas such as business strategy, entrepreneurship, marketing, and human resources, where issues like sustainability, corporate social responsibility, leadership, innovation, recruitment for diversity and equality have come to the fore.

The CEMS community has been contributing to the debate by exploring the way companies respond to the challenge of implementing the UN SDGs. A group of Six Sigma quality accredited business schools including WU Vienna, ESADE, University of St. Gallen and some others recently came together to develop an online course focused on the SDGs. Called the Sigma Responsible Business Course, each school contributed its teaching and research expertise. Ninety students, many from CEMS schools, worked in small virtual teams across institutions to identify best practice examples of companies which were meeting the UN goals. Christof Mishka assistant professor in international management at Wirkshaft Universitat (WU) Vienna explains: “My involvement in teaching about the UN SDGs sprang from the course I developed in responsible leadership.”

One finding of particular relevance to teaching of UN SDGs came from exposing students to cross-cultural experiences. Says Mishka, “it was interesting that corporate best practice can be interpreted so differently depending on where people are from and their cultural background.” He believes that companies need to recognise cross-cultural influences and work to develop a common language and methodology to deliver on global targets.

One difficulty that is already apparent is deciding which of the UN’s seventeen development goals should apply to business and in what circumstances. While individual companies might struggle with large over-arching targets, they need to find which targets are most relevant to their business. Professor Eleanor O’Higgins from University College Dublin comments: “I’m concerned that one target (climate action) is not enough and seventeen are too many especially as some goals overlap with each other.” O’Higgins and professor Lazslo Zolnai of Corvinus University, co-authors of Progressive Business Models:

Creating Sustainable and Pro-social Enterprise believe that capitalist economies need to embrace radical change. Says O’Higgins, “the traditional business model has to be re-thought and re-structured.”

The book illustrates its theme with a series of case studies of companies that have adopted progressive business models. Examples include the Finnish wind energy co-operative Lumituuli which derives its inspiration from SDG 7 – “affordable clean energy” and the Spanish subsidiary of the German insurance company Integralia whose happy and productive workforce meets SDGs 8 and 10 – “decent work and economic growth” and “reducing inequality” and is the result of a recruitment strategy that offers opportunity to disabled people. “What these companies have in common is they are progressive enterprises that seek to serve society, nature and future generations,” says O’Higgins.

Across CEMS Academic Member schools, students have been engaged in a variety of projects to study how companies and individuals are responding to the SDGs. At Nova School of Business and Economics in Lisbon students were asked to study why food and beverage producers were reluctant to draw attention to their corporate social responsibility initiatives when it came to marketing their products. Interviews were conducted with consumers and brand managers of leading companies. What emerged was a “chicken and egg situation” in which the companies felt their efforts to improve CSR would not be translated into public approval and brand awareness.

Pedro Moreira de Lemos took part in the project last year discovered a degree of cynicism among consumers who often regarded corporate claims to boost their environmental credentials as “greenwash”. However efforts to address the SDGs were often genuine and effective. He comments: “One food company was cutting down waste by recovering food that could not be sold because it was out of code. Bananas that could not be presented as supermarket fresh were being recycled as ingredients for sweets or chutney where freshness and appearance were not an issue.” While the company concerned believed that its initiative which met the objectives of UN SDG 12 might be seen as profit-driven, NOVA students believed its approach to “responsible consumption” would be seen as a positive if companies tailored a more relatable, informative and transparent communication strategy to consumers in order to reduce their skepticism.

A similar study was carried out at the University of St. Gallen, where students took part in a three day “boot camp” to brainstorm green marketing solutions that companies could use to promote their progress in meeting UN SDG 12. “Our aim was to apply design thinking to raise awareness and encourage consumers to engage with the need for responsible consumption and production,” says Rotterdam School of Management student Carina Grosse-Entrup. On secondment to St Gallen where she was responsible for marketing the CEMS programme, Grosse-Entrup organised student visits to Geneva-based CEMS partners including the United Nations and P&G.

Part of the “boot camp” involved teams of students conducting a market research exercise in which members of the public were quizzed about sustainability issues. The surprise finding was that half of the respondents had never heard of the UN sustainable development goals at all! Supermarket shoppers tended to look for the cheapest price rather than seeking out organic produce, fresh bread and local products like cheese, seasonal fruit and vegetables.

Changing people’s buying habits could contribute to meeting SDGs by supporting local farmers, thereby cutting down on the wasteful air freight involved in importing exotic foods and the cash crops which are distorting third world economies. Buying closer to home at little extra cost would help reduce reliance on air transport.

Based on prototyping, students designed a mobile phone app which would inform consumers of sustainable choices and alternatives. Some valuable insights guided this design.

Says Grosse-Entrup, “Before you can encourage sustainable buying, you have to make people aware of the choices they have. And you have to make choosing natural products very easy for people. They have to be available at the local supermarket.”

Says Grosse-Entrup, “Before you can encourage sustainable buying, you have to make people aware of the choices they have. And you have to make choosing natural products very easy for people. They have to be available at the local supermarket.”

Globally, one of the main barriers to eliminating poverty and hunger, promoting good health and wellbeing and upholding a universal right to clean water and sanitation is the result of corrupt business practices. For too long major economies have been exploiting the developing world and it is a major part of the UN’s agenda to create a more level playing field.

CEMS Social Partner, Transparency International, campaigns for corporates to make full disclosure of the profits, tax paid and the measures undertaken in each country they trade with. The University of Louvain School of Management and Transparency International Belgium have a long term partnership in which CEMS students learn how businesses are applying UN SDG 16 (“peace, justice and strong institutions) to their public reporting to shareholders and investors. Carlos Desmet, visiting professor in business ethics and responsible leadership, says, “corruption is the single biggest obstacle to meeting the sustainable development goals. It has a huge negative impact on the world economy.”

The practice of offering money or gifts means overseas contracts are not necessarily awarded to the best performing companies and work and materials may be sub-standard. All too often, infrastructure projects in developing countries like hospitals, schools, bridges and railways are substandard.” The issue is so important that the World Bank keeps a blacklist of companies found guilty of corrupt practice on its website.

This academic year, six Louvain CEMS students applied Transparency International’s TRAC methodology to study fifteen of Belgium’s top twenty companies as part of the school of management’s business project. Students analysed how each firm’s anti-corruption policy was working in practice, how transparent the reporting was in the main company and across subsidiaries and finally how companies were communicating financial results country by country.

At the end of three months, the project team requested that senior managers from each company be available at the end of the study to receive the report and discuss its findings. Twelve out of fifteen companies agreed, listening to feedback and promising to act on the findings.

Strict confidentiality was observed and the purpose of the exercise was to provide information to Transparency International in its advocacy role. Guido De Clerq of Transparency International Belgium commented: “Student fieldwork has given us some important insights. As a result, we recommend appropriate compliance policies, tougher monitoring and controls, implementing rules equally across all geographical areas and that clients, suppliers and partners undertake due diligence based on a risk profile.”

Investors are starting to take transparent reporting on sustainability seriously. Meeting the UN SDGs is an essential element of one Swiss investment banks asset management business. WU Vienna CEMS alumna Nadia Brandauer works for this bank in Zurich as a request for proposal writer, a role which involves managing investment portfolios for insurance companies and pensions. Brandauer explains that clients see sustainability as more important than profitability, which can be short-lived. She says: “If a company is managed sustainably it will do better in future in terms of financial returns. According to my company’s Investor Watch, 58 per cent of our high net wealth customers believe that sustainable investment will become the standard within the next ten years.”

Sustainability teams working within the company’s asset management division have put together funds related to specific UN SDGs such as climate change, food production, water and renewable energy. Sustainable investment is now being implemented in all asset classes. Investments are rated according to environmental, social and governmental principles ESG. According to Brandauer, 25 per cent of global assets are managed sustainably (according to ESG principles), but this is set to rise to 50 per cent over the next five years.

The United Nations estimates that $ US 5-7 trillion of annual investment is needed globally in order to achieve its sustainable development goals. Radical change, progressive business models and a sustained focus is needed to help build a future where food, education, clean water and sanitation, healthcare, renewable energy and environmental stewardship are raised to a universal standard.

Case Study / AT Kearney

Recycling and the circular economy

Consumers are looking for brands which are sustainable, and millennials are especially conscious of this, “says Tei Peng global director of social impact at AT Kearney a management consultancy with branches in more than 40 countries worldwide.

A trusted corporate partner of CEMS, AT Kearney advises its clients across different industries and business sectors including governments, educational institutions and not-for-profits to understand and cope with complex social impact and sustainability challenges. As Tei Peng asserts this includes playing an active role in ensuring the UN SDGs are met. It is a long term on-going journey. “We have a policy as a firm that outlines how we make a positive impact on the communities in which we operate.”

Tei Peng sees the circular economy as one of the most promising business models which can help societies achieve the UN sustainable development goals by 2035. Using recyclable components which can be easily replaced or renewed to prolong the life of a product, manufactures design products to be leased rather than purchased outright. Says Tei Peng: “The consumer is buying a service rather than an object. I see recycling and a commitment to reduce waste as the key benefits of the circular economy.

Contributors

Eleanor O’Higgins & Laszlo Zsolnai, UCD Michael Smurfit Graduate Business School / Corvinus

Fabien Castan, Louvain School of Management /TI

Nadia Brandauer, UBS

Alexandra Overath, AT Kearney

Pedro Moreira de Lemos, Nova School of Business and Economics / SBE

Christof Miska, WU (Vienna University of Economics & Business)

C Grosse Entrup, University of St.Gallen

L Katalinich, The London School of Economics and Political Science

![]()